To hear Douglas Stuart talk about his characters, you get the sense that he’s a benevolent creator torn up by the circumstances that corner them and the resulting choices they make. What separates him from the average viewer of an impoverished family riddled with addiction is that he allows them to cling to their dignity even on their most undignified days. He allows them to shine from time to time against the desolate backdrop of council housing in 1980s Glasgow.

Despite the title, the novel often feels like it’s the story of Agnes Bain, or perhaps, the Agnes Bain Show might best describe her outsized rages against the men in her life when she’s spent the morning (and afternoon and evening) drinking Carlsberg Special Brew. No one is more transfixed by this show than her youngest child, Shuggie, left to hide their benefits book and care for his mother by age ten after multiple father figures and two older siblings leave her to drink herself nearer death.

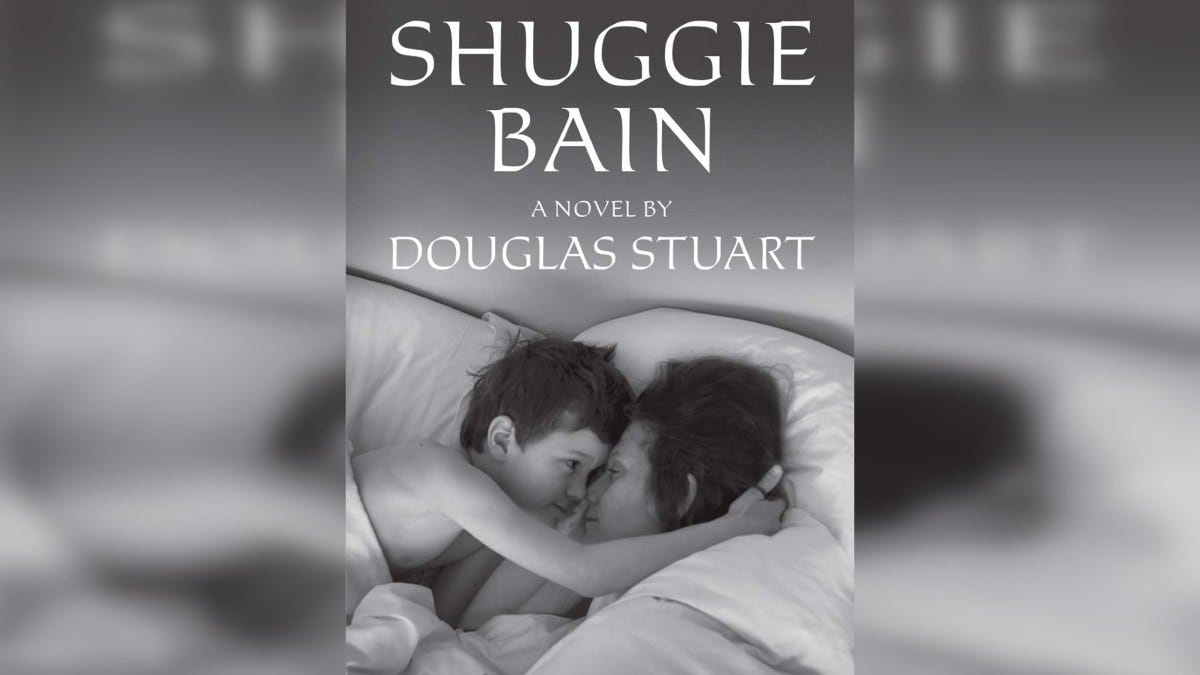

In truth, the story’s about both of them, and we need glimpses into Agnes’s past to make guesses at what might be in Shuggie’s future. It’s the bond between mother and son stretched to its limit but never broken, two people who desperately need each other, helpless to save one another.

Shuggie worships his mother. He’s pegged as “no right” from his earliest days, and the homophobic setting of 1980’s Glasgow makes him and his mother natural allies despite her inability to care for her brood.

It’s in their shared ostracism that their bond deepens, and it’s in Agnes’s daily struggle that Shuggie will find the roadmap to survive his own. In much the same way that his schoolmates never tire of harping on his differences, Agnes is shunned to the bottom of the pecking order in their public housing because, despite being on the dole themselves, the other women are more than happy to turn up their noses at the “alky hoor” next door.

As Agnes and Shuggie spend more time together, she all too happy to have someone steady on his feet to collect benefit stamps and he just as keen to skip the punishment waiting at school, there’s ample amount of heartbreaking neglect and tender love. One evening as Shuggie dances a reinterpretation of a Janet Jackson routine for his mother, he realizes too late that he’s in full view of the front window that faces the street and the bullying clan that lives across the street. As his body spins to a halt and his face screws up with tears, Agnes insists that he keep dancing, finish the routine, and continue listening only to what his hear wants.

She was no use at maths homework, and some days you could starve rather than get a hot meal from her, but Shuggie looked at her now and understood this was where she excelled. Everyday with the make-up on and her hair done, she climbed out of her grave and held her head high. When she had disgraced herself with drink, she got up the next day, put on her best coat, and faced the world.

It’s the rare insight Shuggie gleans from his mother. That this, holding her head up high in the face of ridicule, is her superpower, that she’s dead serious about continuing the dance, and that she’s right.

We don’t get many glimpses of Shuggie making his way through Glasgow after he leaves his mother’s house, but he’s the third and final child to make it out, the one most attached to his Mammy, and it’s clear he’ll have many more questions to ask of himself and his city as he coexists with many others who might take a wee drink from time to time.

Agnes and Shuggie need each other, but ultimately, Agnes needs the drink more than she needs Shuggie. And that’s something he’ll be left to answer long after his mother takes her final sip.

It’s on my list, Jacques—Thanks! Am shooting for 100 books this year and then we’ll compare notes—Red